‘The Beginner’s Guide’ Review

Spencer Smith ’19 / Emertainment Monthly Staff Writer

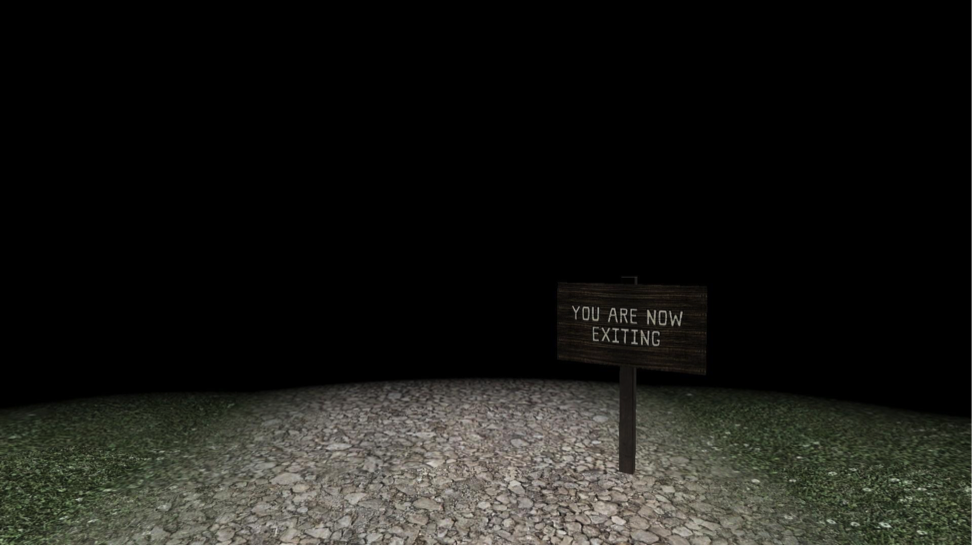

There’s a point early on in Davey Wreden’s The Beginner’s Guide, his self-proclaimed compilation of work of a person he loves, where you play a game that takes 15 seconds to complete. You walk on a path and can’t see ten feet in front of due to a fog, you pass a sign that says “You Are Now Exiting,” and it ends. Wreden’s game is to video games what Exit Through the Gift Shop is to documentaries. It’s a unique blending of video game, true story, expressionist art, and interactive movie. The Beginner’s Guide is all of these things, and yet it’s also something else, something harder to put your finger on, something that has you question personal value, perception, validation, and isolation. Wreden hasn’t just created a game almost, if not equally profound as his previous work: The Stanley Parable, but also something wholly different. Wreden’s latest work is a powerful subjective experience that blends techniques, genres, and art forms into something that’s emotional, personal, and powerful.

Wreden opens the game by claiming it to be a compilation of games by a game designer named Coda, who he displays great interest in. The whole game plays out with Coda’s games as Wreden narrates, explaining his strange relationship with the ambiguous designer. Coda’s games are deeply experimental and — according to Wreden — self-reflective. The question of how true the story is remains up to the player, but it doesn’t truly matter as the game becomes more subjective than just a retelling of a true story. Tragedy, confusion, and perception are all toyed with, resulting in a narrative story and personal experience. Wreden narrates the whole game, which blends narration, interview, and performance art into something utterly unique. Is he just acting to elicit response, or was he recording his inner feelings? It hardly matters though; his performance, confessions and the worlds he puts you in are all incredible. The Beginner’s Guide is a deep personal experience for Wreden, as it will be for anyone who’s had issues with identity, self-gratitude, and a struggle for meaning.

The games within The Beginner’s Guide are experimental, even unplayable vignettes of games. Designed in the Source Engine — an engine that’s still used despite being 11 years old — the games are each explained by Wreden, and sometimes he helps make them playable. In one part, the player travels up some stairs, the game gradually slowing them down to a nearly immobile crawl; Wreden then gives the player the option to go back to normal speed to reach the top. Wreden’s narration on the games seems to give us insight into the creator’s mental state. Wreden says that he learned who Coda was largely through his games, as they seemed to reflect Coda. There are even dates before each level to enhance the narrative aspect. In the games, sometimes there’s a dialogue tree, or a gun, or switching “characters” — there’s no NPCs in the games. All are deeply experimental; even without Wreden’s narration, which you can turn off, they would stand as fascinating emotional experiments. Like an experimental film, they’re utterly removed from mainstream design and evoke emotion from their design. And like a good experimental film, it doesn’t preach how grand it is, it simply is. Most of the games are corridors, houses, wide-open spaces, or simple geometric shapes. The game doesn’t try to make you think it’s deep, it allows you to feel it. Players might want to play through the game with and without the overarching narrative, to see how the tone of the game changes.

However, back to the narration; it’s a powerhouse. The Beginner’s Guide speaks on multiple levels of meaning. On one hand, it’s about the interaction between a game developer and a player. Wreden details the complex relationship he has with Coda, bordering on fan and creator. It’s possible that Wreden based the game on the unexpected popularity of The Stanley Parable; one could imagine the feedback and demand of outspoken fans represented by the relationship he has with Coda. On the other hand, it could also be interpreted as, well, interpretation. At one point our perceptions of the game shift, where the player is suddenly, and quite intensely, forced to wonder whether their interpretations so far were from Coda’s games or Wreden’s narration, or something else entirely. The point is that The Beginner’s Guide could be any of these and more.

Simply making a game to be different doesn’t guarantee quality. There are several games that are nothing more than “artsy” attempts to cash in on the market. Yet The Beginner’s Guide goes beyond a simple “whoa, this is really weird” and delves into something deeper in both its themes and design. It’s safe to say that a lot of players will never have played a game like The Beginner’s Guide, and the gaming world has had its share of bizarre, experimental games. For the 8th or 9th game, the beginning screen tells you to close your eyes for maximum effect. After the first failure, Wreden has you open your eyes to see that you’re on a spaceship with the games’ motionless TV-headed mannequins and the recurring door, now huge enough to collide with the ship. You get dialogue options and you find that the only way to stop it from hitting you is to say something honest, so you say something like this: “I can’t keep making these”. It gets more self-deprecating and disturbing, but you start to see this kind of disturbing psychosis in the creator and possibly yourself. It’s an emotional moment of revelation in the narrative, but at the same time you, the player, get this uncomfortable feeling as you openly say these things. While the narration is what connects these games into a kind of narrative, the games themselves elicit the player’s emotions. It’s personal both with and without narration, and it ultimately all comes down to who the player is and how they perceive their experience playing the game.

The term “video game” can be hard to apply to games nowadays since not all pieces of interactive media are “games.” Now, The Beginner’s Guide is a new trump card for the “Games are Art” argument. Wreden has made something different from, and yet essentially still, a video game. It functions as many things, but as a game it fully achieves its intent. It brings you closer to the experience; it delves into personal issues of both creator and player. It’s impossible to talk about The Beginner’s Guide’s technical aspects, or even if it’s “fun” to play, because it isn’t that kind of game. It’s not a game that depends on mechanics; it simply presents you with an experience up to your interpretation. You can imagine that of hundreds of people playing this game, they could all have had a different experience. Although it is linear, it’s ultimately up to the player to decide how they feel about the journey.

The game clocks in at around 90 minutes. It’s a short game, but players might find themselves revisiting The Beginner’s Guide. Why? Well, one of the great things about art is that it’s so subjective that anyone can interpret it in any way they want. There’s a documentary about The Shining’s true meaning ranging from Kubrick faking the moon landing to the Holocaust. That is great art in nutshell; you can draw conclusions one day and find new meaning in the next. The Beginner’s Guide thrives on this kind of subjectivity; it can mean many things but it leaves it to the player to decide. The Beginner’s Guide blends so many different formats together but ultimately results in a game experience like no other, something widely enjoyed but deeply personal. And isn’t that great? When you find something so unique not only because of what it is, but because of what it means to you?

Rating: 5 stars