Review: 'Finding Dory' Provides an Unforgettable Experience

Meaghan McDonough ‘17 / Emertainment Monthly Staff Writer

Did it need a sequel? Not really. But thank God it got one anyway.

The sequel, Finding Dory, centers on the funny but forgetful character of Dory (Ellen DeGeneres) who suffers from chronic amnesia yet still managed to remember the one address that helps Marlin find his son in Finding Nemo. It seems almost counterintuitive to make a movie about Dory: she can’t remember anything for more than a few minutes, and much of her purpose in the original movie was to move the plot forward. Yet Finding Dory manages to do the impossible: make a character out of a caricature. Not only is Dory still funny but forgetful, but she’s also got a perspective, a purpose, and—most tellingly—a past. Finding Dory is, at its core, Dory’s origin story—and it manages to be that while also being a story of going home.

But Finding Nemo was also more than just a family-friendly adventure through the Great Barrier Reef, and so is its sequel. While Finding Nemo showed the struggle of being a parent to a child with a disability, Finding Dory takes it a step further. Dory’s chronic amnesia is difficult to deal with, but not debilitating. The film not only shows how Dory can overcome it, but also how she uses it to her advantage. Not only that, but the film shows how by looking at the world the way Dory does can be beneficial to other’s as well. This sentiment is epitomized in a scene toward the end of the movie where Nemo asks Marlin, “What would Dory do?” Together, the two clownfish work to view the world through Dory’s eyes, which actually helps them to escape captivity and get back to their friend. It’s a powerful statement in favor of the theory of neurodiversity, and it’s really something beautiful.

In a way, that’s what the whole movie—heck, the whole franchise—is about. Neurodiversity is an approach to learning and disability that explains neurological differences as natural part of humanity, and that it should be respected as a “difference” as opposed to something that needs to be fixed. It looks to recognize the value in difference—the values of thinking like Dory, to just keep swimming—and how supporting these differences can better society.

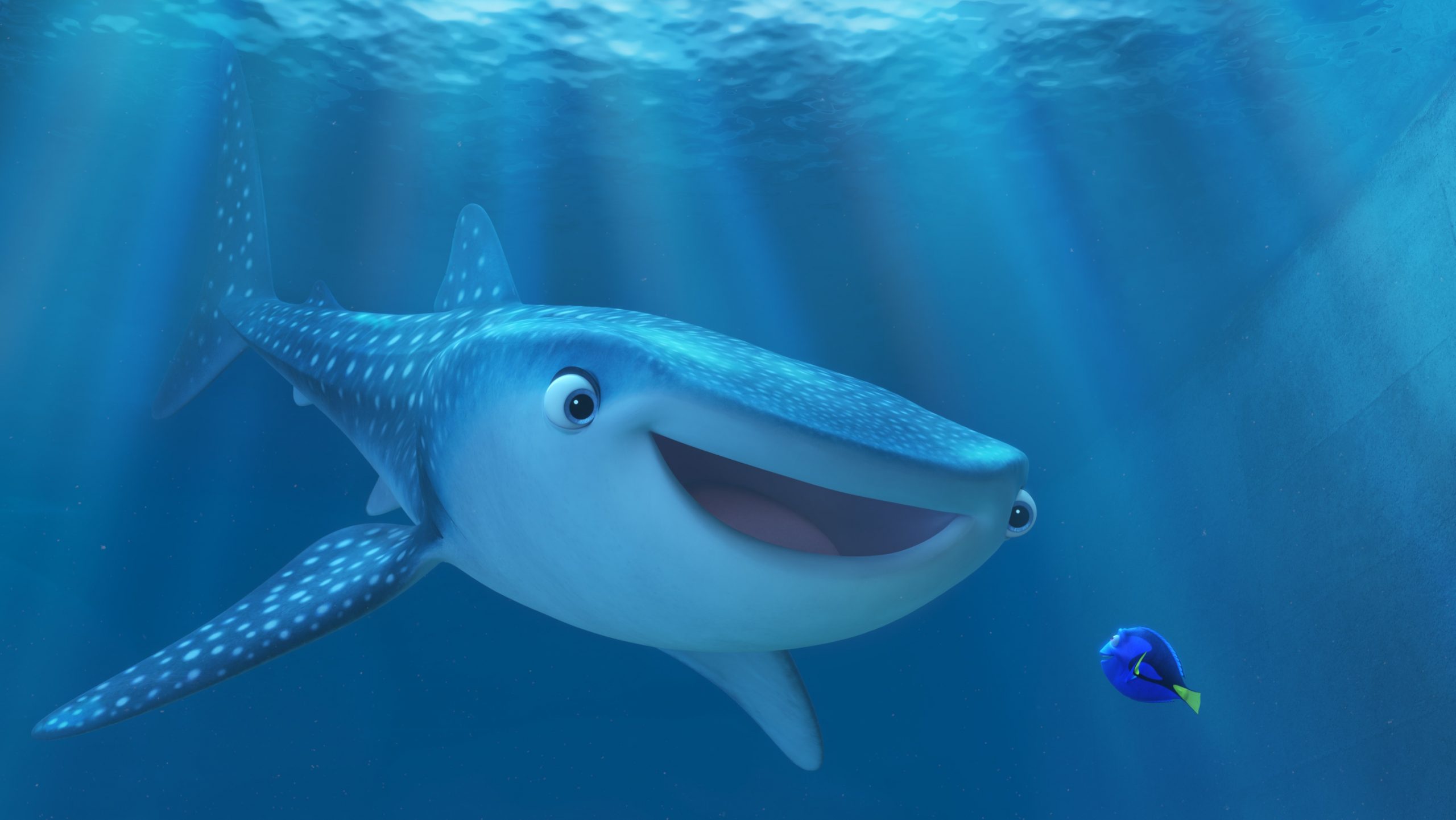

Of course, like Finding Nemo, there’s a whole bunch of other disabilities represented across the sea creature spectrum. There’s a whale shark named Destiny (Kaitlin Olson) who is short sighted; Bailey (Ty Burrell), a beluga whale, who claims to have lost his echo locative abilities due to head trauma; and Hank (Ed O’Neill), an octopus who lost his arm and also has an intense fear of the ocean—and that’s just to name a few. All of these characters, and more, help to give Finding Dory the same (if not more of) charismatic color claimed by its predecessor.

That being said, DeGeneres’ sad, sanguine, and serious moments as Dory are nothing to ignore. She turns Dory—a relatively simple sidekick—into a three-dimensional, well rounded, deep-feeling and sympathetic character. Andrew Stanton’s script is heavy handed at times, but DeGeneres makes you at least want to believe it all. There are moments in this movie that can actually reduce a millennial to tears, and a big part of that is DeGeneres’ doing. The rest of it, of course, is nostalgia met with beautiful animation. And the animation is really beautiful. If you can’t appreciate Finding Dory for the plot—which anyone with a heart should be able to—the very least you can do is recognize how far Pixar has come in thirteen years.

Finding Dory put it best in the final word of its film. Dory, staring out into the vast expanse of blue at the edge of her reef utters a single word: “Unforgettable.” Staring back at the screen as the credit’s role after the movie’s 110-minute run, it’s impossible to disagree.

Overall rating: A

Watch The Trailer: [embedyt] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MKJA-VLpiCo[/embedyt]