The 10 Best Films of 2023

John Maescher ‘27 / Emertainment Monthly Staff Writer

- Showing Up (dir. Kelly Reichardt)

Kelly Reichardt has spent almost three decades as one of our greatest and most insightful filmmakers, and yet her films always seem to fly a little too far under the radar, never quite receiving the widespread appreciation they deserve. Her latest film Showing Up suffered largely the same fate, first premiering at Cannes all the way back in 2022 before quietly being released to the public a whole year later with little fanfare. As a result, it hasn’t gotten nearly enough recognition as one of 2023’s very finest films, another stellar entry in a filmography full of them. Showing Up follows Lizzy (Michelle Williams), a Portland, Oregon-based artist navigating the minute frustrations of her daily life as she prepares for a career-defining exhibition. It’s a wonderful film about finding self-fulfillment and satisfaction through creating art, and knowing that despite whatever troubles we have to push through in our day-to-day lives – whether it’s dealing with a demanding landlord who’s also a rival artist (Hong Chau), stressful deadlines, or family struggles – there will always be the reward of the freedom found in the act of creation, and the validation of those who show up for the art.

- The Holdovers (dir. Alexander Payne)

It’s not every day that a film comes along that earns the “instant classic” label, but Alexander Payne’s warm, bittersweet Christmas dramedy feels destined to join the perennial holiday rotation for the foreseeable future. A film that’s not only set in the 1970s but goes to painstaking lengths to resemble a film directly pulled from the time period, The Holdovers is much more than simple pastiche; it’s Payne’s most affecting and sensitively handled work in a filmography full of them. We come to care deeply about our main characters Paul (Paul Giamatti), Angus (Dominic Sessa), and Mary (Da’Vine Joy Randolph), as these three flawed people find common ground with each other. Everything in the film rings true and genuine. Life lessons are learned, but there are no easy fixes or answers. Instead, it’s about three broken people simply coming to an understanding of each other and finding a catharsis they didn’t know they were looking for, which is sometimes exactly what we need when we’re lonely and have no one else to turn to. The Holdovers is a delightful watch for its wry sense of humor and cozy aesthetics, but it’s the poignant emotional truths and rich depths of its characters that linger after the credits have rolled.

- May December (dir. Todd Haynes)

There are few working American filmmakers smarter and sharper than Todd Haynes, whose thorny, transgressive May December marks his best work since 2015’s Carol. The film is a masterful balancing act of lush Douglas Sirk-esque melodrama, high camp, and a much sadder and more devastating undercurrent; it’s a tonal tightrope that’s incredibly hard to pull off and could easily collapse in the wrong hands, but Haynes handles it gracefully. There are so many layers to unpack, whether it’s how it functions as a satire of method acting and the absurd lengths actors will go to in order to “get into the character”, a commentary on the exploitative nature of true crime stories and America’s fascination with them, and a sensitive exploration of sexual abuse and its lingering effects throughout a lifetime. Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore both turn in exemplary work, but it’s Charles Melton who provides the heart and soul of the film, giving an astonishing performance as a man who’s only just beginning to confront the tragic truths of a life he was never able to properly understand, having been robbed of a proper adolescence and gaslit into a facade of idyllic perfection.

- Ferrari (dir. Michael Mann)

Michael Mann’s illustrious filmography has long been defined by steely professionals fully devoting themselves to their work and craft, in turn closing themselves off from the people around them and selling their souls to capital. So it naturally makes sense that Mann would eventually turn his camera to the life of Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver), specifically zeroing in on a period of a few months in 1957 when Enzo was forced to balance the constant attention from Italian media, his dueling loyalties to his wife Laura (Penélope Cruz) and his mistress Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley), and the looming pressure of creating a car for the upcoming Mille Miglia race, all while the grief of his son Dino’s recent death hangs over him at every turn. In several ways, Enzo feels more like a directorial stand-in than any of Mann’s other protagonists, mirroring Mann’s perfectionism and precise craftsmanship as a filmmaker. It’s yet another exceptional work from a master, as the classical stoicism of the domestic melodrama and the dynamic excitement of the racing sequences form two halves of a complete, brilliantly crafted whole.

- Asteroid City (dir. Wes Anderson)

Wes Anderson has steadily spent his career crafting his distinct brand of meticulously constructed dioramas that have only become more formally radical and complex as the years have progressed, and the staggering Asteroid City marks one of his most innovative and invigorating ventures yet, pulling back the curtain on the entire artistic process behind those dioramas. We follow the parallel stories of extraterrestrial revelations at a children’s science convention in a 1950s desert town, and the production of a stage rendition of that very same story, which is itself being broadcast on a ‘50s television show. Aesthetic lines are clearly drawn between the dueling narratives, with the former told through eye-popping pastel colors and widescreen postcard-esque imagery, and the latter shot in stark 4:3 black-and-white compositions. Eventually, the boundaries begin to blur, and Anderson jumps from place to place in his nesting doll structure to explore why we use art and artifice to process the unknown. A key moment comes when one of the stage actors (Jason Schwartzman) struggles to understand the meaning of the play he’s performing, to which he receives the response: “It doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story.” Asteroid City poses all kinds of questions about art: why do we make it? Why does it matter? Why do we keep going even when we don’t understand why? What does it all mean? Who knows? Do we need to fully understand it when it’s the feeling that counts? In making art, we find ways to confront the unknowable and provide catharsis for both ourselves and whoever else out there in the audience it may resonate with. Just keep telling the story, and the answers will lie in the eye of the beholder.

- The Zone of Interest (dir. Jonathan Glazer)

The Zone of Interest is Jonathan Glazer’s first film in ten years since his masterfully unnerving Under the Skin, and here, Glazer expands on formal ideas from that film to create what’s simultaneously his most restrained and horrifying work yet. It’s a film where the horrors lie in what we don’t see and what we constantly know is just outside the boundaries of the frame. The title refers to Auschwitz in 1943, where camp commandant Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) and his family live comfortably on the direct border of the camp wall. Glazer never takes his camera over to the other side of the wall, instead having us follow the daily minutia of the Höss family as unspeakable atrocities take place right next door. Occasionally, the sounds of screams and gunshots drift casually into the soundscape, forming some of the most chilling sound design in any recent film. We are left to wonder how it’s possible for this family to sleep at night; how can they tune out these sounds and turn a blind eye to the genocide they’re complicit in? The Zone of Interest is a film that forces us to stare evil directly in its face and witness the chilling banality with which evil is so often carried out, studying the complicity and compartmentalization of those who perpetuate these atrocities. It’s an imposing and rigorous experience that chills to the bone and lingers in the brain.

- John Wick: Chapter 4 (dir. Chad Stahelski)

2023 was an outstanding year for theatrical experiences, but in terms of pure euphoria and exhilaration, it’s still tough to beat what John Wick: Chapter 4 brought to the table. Over the course of the four John Wick films, Chad Stahelski and co. continued to hone their skills and up their action game with each passing film, and the fourth and (presumably) final installment sees them reach the absolute height of their powers, showcasing a perfect culmination of everything they’d been building towards. The film is almost three straight hours of some of the most exquisitely crafted action filmmaking to ever grace the silver screen, barely ever stopping for a breath while jumping from set piece to set piece. Each action sequence is expertly choreographed and intricately staged in ways that no Hollywood action film has been since maybe Mad Max: Fury Road in 2015, with an unmatched fluidity and balletic grace in their movements. It’s rare to see something with such an unending commitment to consistently one-upping itself; by the time the film reaches its bewildering, exhilarating climax in Paris, all that’s left to do is simply marvel at the sheer maximalism on display. It’s a new gold standard for Hollywood action filmmaking.

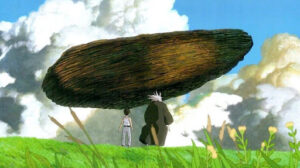

- The Boy and the Heron (dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

The Boy and the Heron may not end up being the final film from legendary Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki like it was initially touted as, but it’s the kind of film that could only be made by a master in the twilight years of their career. It’s a gorgeous, poetic reflection on legacy and the things we leave behind, concluding that maybe it’s best to move on, let the past go, and leave behind what can’t be changed. Much of it feels like classic Miyazaki – the lonely child whisked away on a fantastical journey, the adorable little creatures, the painterly animation – but it also feels like uncharted territory at the same time. It’s his most enigmatic work yet, relying more on abstract dream logic than narrative logic, but its wonders lie in its messy, unwieldy ambition. Every frame and every turn of the journey overflows with beauty and imagination. Miyazaki is painting on the largest and most sweeping canvas possible, and much of it may be confounding and mystifying at first glance, but going along for the ride makes for an immensely rich and moving experience. The Boy and the Heron doesn’t give us direct answers to the questions it raises; rather, it lets us find our own. And Miyazaki ties it all together in the most emotionally satisfying way he can, with a final image of profound beauty and simplicity.

- Killers of the Flower Moon (dir. Martin Scorsese)

At 81 years old with one of the most iconic repertoires that any filmmaker could dream to have under their belt, Martin Scorsese doesn’t have to prove anything to anyone, and yet he’s still finding ways to push himself and find new heights as an artist. Adapting David Grann’s 2017 nonfiction book about a string of mass murders in Oklahoma’s Osage Nation in the 1920s, the monumental Killers of the Flower Moon does away with Grann’s investigative procedural structure in favor of an inquisitive study of evil and the circumstances that allowed these atrocities to happen. It’s a blistering reckoning with one of the darkest sins in American history, telling a story that was historically ignored and covered up for far too long and bringing it to life in a brutally honest, devastating masterwork. Scorsese immerses us in evil from the beginning, putting us in the passenger seat as the hapless Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) is guided by his powerful uncle William Hale (a terrifying Robert De Niro) into slowly poisoning his Osage wife Mollie (Lily Gladstone, in one of the greatest screen performances in years) to inherit her oil rights. The film’s sprawling 200-minute length plays like a funeral procession, a steady, sickening accumulation of dread and inevitable atrocities that leaves us to wonder how this ever could have happened in plain sight for so long. And then there’s the breathtaking coda it builds to, directly acknowledging Scorsese’s own limitations in telling this story as large-scale entertainment. It’s a deeply sad, mournful masterpiece that reckons with the horrors this country was built on in ways that few Hollywood films, if any, ever have.

- Oppenheimer (dir. Christopher Nolan)

The dominance of Oppenheimer in 2023 feels like a miracle. A three-hour epic about the creation of the atomic bomb and its awful legacy, told mostly through scientists and politicians talking in offices and courtrooms, somehow made over $950 million and became a cultural touchstone. And yet Christopher Nolan’s towering film speaks for itself, turning this material into the most thrilling cinematic experience of the year. It is a staggering feat of craft and construction, a seismic monument that grapples with the complete weight of a creation that’s simultaneously awe-inspiring and horrifying, and captures the haunted, inscrutable interiority of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) as he’s forced to live with the consequences of his creation. Nolan takes us into Oppenheimer’s mind, showing us his quantum visions of a “hidden universe” and conveying the contrasts of a man who was both an undeniably brilliant scientific mind and also responsible for the most destructive invention in human history. It’s a bleak and harrowing experience, reckoning on a massive scale with the psychological tax and turmoil inflicted by one of the most consequential, horrific decisions America ever made. And yet it plays like an exhilarating, white-knuckle thriller, masterfully edited by Jennifer Lame as it moves at a breakneck pace through an overwhelming stream of information and incident. In terms of pure craft, it’s a flawlessly assembled achievement in every department, from Hoyte van Hoytema’s breathtaking 65mm and IMAX photography, to Ludwig Göransson’s instantly memorable score, to the all-star ensemble cast reminiscent of the prestige Hollywood epics of yesteryear. Oppenheimer is the kind of monumental feat that only comes around once in a blue moon, and will surely be remembered as the definitive cinematic work of 2023.