A House of Many Doors

James Sullivan ‘22 / Emertainment Monthly Staff Writer

A House of Many Doors is a top-down text-heavy exploration RPG, written and designed by Harry Tuffs, illustrated by Catherine Ungar, and published by Pixel Trickery with the backing of Failbetter Games. In it, you’re tasked with exploring the macabre expanse of The House- a parasite dimension in the shape of an endlessly expanding mansion proportioned for giants. For untold thousands of years, The House has been transporting people, objects, and even entire civilizations from other dimensions and depositing them within its darkened rooms at random; over time, these abductees have built dozens of thriving city-states on the floors of long-abandoned parlors, sustaining themselves by scavenging materials that The House places within itself at random.

The player captains a velocipede- a multi-legged mechanical train that skitters through the dark of The House, delivering cargo, passengers, and information between far-flung city-states. After a brief combat tutorial in which you and your eight hapless NPC crewmates do battle with privateers to recover a box full of your stolen memories, you’re set loose to go about your business; looking for trading work with the local powers, following up on leads provided by your companions, and investigating the source of your character’s bizarre prophetic dreams.

You’ll pilot your velocipede to the furthest parlors of The House in search of a fabled means of escape. Along the way, you’ll unravel conspiracies, hunt down fugitive cities, find work as a bad poet, rig elections, go insane and resort to cannibalism, euthanize chained gods, engage in vigilantism against the Omni-pope, and have carnal relations with a sentient oil rig.

You know. If you want.

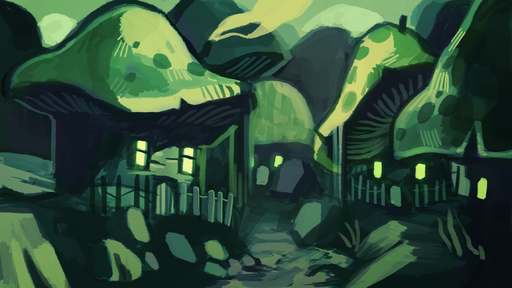

AHOMD is fundamentally centered on exploration. The game imports the basic gameplay of Sunless Seas and its sequel Sunless Skies – both by Failbetter Games, who threw their creative and financial support behind AHOMD’s development. Players maintain a birds-eye, top-down view of their velocipede, navigating through a massive grid of interconnected chambers populated by randomly generated landmarks, enemies, and physical obstacles. Nearly a hundred cells in the grid are occupied by fleshed-out locations – cities, landmarks, holy sites, ancient ruins – which the player can navigate using extensive, reactive dialogue trees. Locations are granted their visual character with gorgeous impressionist paintings by the talented Catherine Unger, which act as a backdrop to your textual romp through each locale.

In keeping with the focus on exploration, character advancement is largely separated from the game’s (somewhat lackluster) combat mechanics. Players gain apprehensions (read: experience points) not through wanton slaughter, but by discovering new locations, advancing their relationships with their crew, partaking in strange experiences, and by accruing memories of strange, wondrous, and unsettling events, which in this setting are redeemable trade goods that can be extracted from one’s mind via magical spinal tap.

You might make money off trade deals, but the real power in this game comes from throwing yourself off the beaten path in search of strange relics and undiscovered hideaways. Compared to the games it draws inspiration from, AHMOD is pretty loose in what it asks of you in terms of survival mechanics and resource management. You only have two main resource bars, fuel and sanity, and the former is both weightless and cheap. Now all you need to worry about is your ever-present, inexorable slide towards total insanity, mutiny, and self-destruction out in the endless dark.

The game relies heavily on the use of prose description to relay the finer details of the world, but it rises to its own challenge – everything from the bizarre high-level worldbuilding down to the flavor text accompanying each inventory item is relayed in a tone that’s deadpan yet evocative, and often gut-bustingly funny. Anyone who enjoyed Douglas Adams, Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman, and China Mieville will find themselves at home here.

The game exploits the multidimensional nature of the setting to seamlessly blend together plot hooks and concepts from every conceivable genre; One minute you’ll be hunting vampires through a city where the walls bleed constantly; the next you’ll be exploring a city built in the ruins of a crashed starship, or treading lightly through a mirror-covered city wracked by civil war between the people and their own sentient reflections. The characters you can encounter and recruit to your party are no less memorable in concept or execution. You might find yourself in the company of Abbas Salam, a man who was born his own twin, occupying two bodies with one mind, or Banjo Smuggs, the relentlessly cheerful zombie mobster, or Jhang Ba Sho, the mushroom revolutionary.

AHMOD only has two real failings. The first has to do with world navigation; the randomly generated grid system likely saved the developers an enormous amount of time at the expense of an enormous amount of yours. The world isn’t that interesting to navigate – bar minor aesthetic alterations based on the region of the map you’re in, the rooms are all more or less identical. The landmarks become background noise. Encounters with enemies provide interesting flavor text…. the first few times, at which point resolving the same dialogue tree again and again begins to lose its luster. You’ll find yourself holding down the forward key for minutes at a time, your progress interrupted every few seconds by the transition between cells. In many games, it’s about the journey, not the destination. This is not really one of those games.

The second major failing is the combat system. The game features a ship-to-ship turn-based combat system, initiated upon encountering an enemy vessel out in the wilds of The House. You take turns exchanging volleys of weapons fire, micromanaging the positions and duties of your crew, and performing evasive maneuvers. There are a range of different weapons systems you can equip your velocipede with, ranging from artillery to golem canons, to weaponized acidic glands. There are even mechanics to form boarding parties and attack enemy crews directly.

But all this depth is undercut by the fact that most fights, win or lose, can be resolved in only two or three rounds of straightforward hammering on the enemy with standard weaponry. You don’t need to get fancy, and since you can only switch out your equipment while in a port, you’re incentivized to stick to generalist weapons that’ll do okay in any situation instead of branching out. Some of the enemies have unique attacks or behaviors, but on the whole, combat feels same-y and, even worse, visually underbaked. Everything in the combat interface is represented by silhouettes and minimalist sprites. Beyond making combat uninteresting to look at, it also makes for a rough time from a user interface perspective. Have you ever dreamed of frantically trying to micromanage the positions of six indistinct orange pegs while under fire from a gigantic wasp-tank full of insectoid slavers? Well, here’s your chance.

However, these failings are so egregious only because they act as an impediment, wedged in between you and your next marvelous discovery. Overall, A House of Many Doors is an endlessly entertaining and engrossing dive into an utterly bizarre world rife with adventure, bogged down at only a point or two by rough implementation. It’s a hidden gem well worth the asking price.