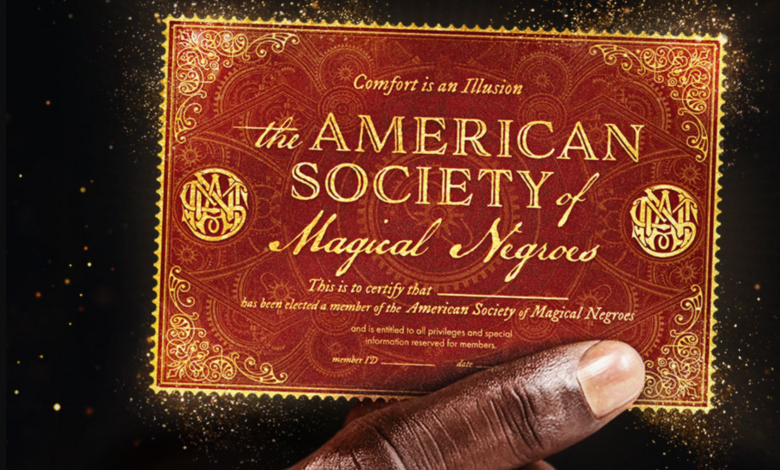

The American Society of Magical Negroes Saves The Damn World… Through Black Subservience?

Abby Meacham ‘25 / Emertainment Monthly Staff Writer

“Some believe that Magical Negroes only exist in stories,” reads the onscreen text in the first few seconds of The American Society of Magical Negroes. “Others know the truth.” The truth in Kobi Libii’s 2024 film debut is that unbeknownst to the masses of sad white Americans, a secret black society exists with the sole purpose of making white people’s lives easier.

For those unfamiliar, the Magical Negro takes the form of a minor black character in a film or TV show who helps the white main character find their purpose and… that’s it. No backstory, no depth, and sometimes no name at all. They usually have magical powers, and they offer plot-relevant advice no matter the circumstances, delivering metaphors and sage wisdom with a gravelly voice and a thick Southern drawl (where the film actually takes place is irrelevant; the Magical Negro always sounds like they’re fresh off the streets of N’awlins).

In Libii’s film, the Magical Negro is a young biracial man named Aren (Justice Smith) who takes up the mantle when Roger (David Alan Grier) offers to show him the ropes. As he sinks further into his duties as a willful stereotype, he meets Lizzie (An-Li Bogan), but as their relationship develops, Aren must choose between who he is and who he needs to be to survive in the world as a black man.

My initial temptation is to offer the same statement made about many black satirical films, which is that The American Society of Magical Negroes “has a lot of important things to say.” But I don’t think that’s exactly right. This film is saying a lot of things, some of which are important.

There are a few things this movie gives plentifully. Smith and Bogan make great work of the script, delivering their lines with a natural clumsiness that is genuinely charming. Smith tends to play characters with a lot of nervous energy, and this role is no exception, but it does work in his favor. The background members of the Society also support the humor very well; in particular Moe Irvin and Gregor Manns, who have small roles as previous Society graduates, fully commit to their scenes as Magical Negroes. The camerawork is nothing special, but it doesn’t make the viewing experience worse. Unfortunately, none of these things change the film’s true flaw, which is its concept.

The American Society of Magical Negroes is part of the wave of Black satire that has emerged over the past few decades. The satire exists to varying degrees, from the absurdism of Sorry To Bother You (2019) to the uncanny humor of Get Out (2017). But there is always something to ground these films in reality, and that is what makes their themes so potent. In a movie the “white voice” functions as a superpower, but in reality many black people do use a “white voice” in professional settings. Wealthy white liberal families aren’t actually transporting their consciences into black bodies (I think), but the passive-aggressive way Rose’s family treats her black boyfriend Chris is so realistic that it can invoke a visceral response. Beneath the satire, there must be some kind of truth.

But the subservience of the Magical Negro, when applied to the real world, stops becoming a joke at the expense of a white audience. Instead, the joke is at the expense of black people who, when faced with conflict or confrontation, revert to a “palatable” version of blackness. To be fair, the film tries to touch on this through Aren, who is repeatedly called out for his meek nature and lack of self-confidence. As aforementioned, Smith is good at playing characters with such a demeanor. However, we are never shown a version of Aren who isn’t like this all the time. In his first interaction with Lizzie, a fellow person of color, he stammers his way through an apology and crumbles the second he thinks he’s made her uncomfortable. He’s easily intimidated by Roger’s overt friendliness when they first meet. Who is Aren when he’s not appeasing white people? Well, he’s appeasing everyone else.

Whether Libii intended it to be the case or not, the Society is saying that the solution to systemic racism is black passivity. Now, maybe the film is also saying that systemic racism can be fixed if black people are confident, unsubmissive, and willing to call out racist behavior, which is true— to an extent. But neither of these options are solutions; they’re reactions. Insisting that they are cures to systemic racism is like insisting that the cure for an infection is not antibiotics, but the fever that it brings.

And frankly, we were robbed of a film about a black wizarding world.