Beau is Afraid, and So am I

Molly Kurpis ‘25 / Emtertainment Monthly Co-President

Emerging from the twisted family of Hereditary (2018) and the acid-induced trip from Midsommar (2019), director Ari Aster amalgamated his strengths from these previous films for his newest project, Beau is Afraid (2023). Aster has already claimed his position as one of the strongest modern day horror filmmakers. His interest in psychedelic realms, broken characters, and contradicting morals make for surreal-like endeavors that surprise and haunt his audience. Indeed, the surrealist aspects of physiological horror meet their match in Aster’s newest film. Beau is Afraid follows the story of Beau (Joaquin Phoenix) as he attempts to navigate his way home. Battling his worst nightmares through an anxiety-riddled lens, the three hour film serves as an odyssey to Aster’s strengths, challenging any preconceived notions of horror at large. Beau’s interactions with other characters become more and more estranged through each setting, which is the only constant variable in the film. Although Beau as a protagonist is passive in nature, his relationship with the world at large is put to the test.

Spoilers ahead.

The first act of the film introduces the audience to Beau through a day in his life, establishing his character and his core personality. A firm and direct relationship is established between the viewer and the protagonist. Beau’s neurotic behaviors and quirks drive his decision-making, or lack thereof, as he attempts to ready himself for a visit with his mother. Detail-saturated scenes allow the audience to understand his distrust of his environment, his convoluted actions making for semi-surreal worldbuilding of his rundown apartment in a dangerous neighborhood. His hesitancy to travel home serves as a catalyst for his actions. Beau’s luggage is stolen, and his apartment is ransacked. He angers one of his neighbors by ‘blasting music,’ yet he hears nothing. He is afraid of leaving his apartment, but he is also afraid of hurting his mother. He is paranoid, and his paranoia helps build a distrustful, confusing world. He eventually tries to call his mother but learns that a UPS worker found a female body decapitated – likely his mother. Beau sprints barefoot into the street and is run over by a truck, propelling the audience into the second act.

Beau is brought to Roger (Nathan Lane) and Grace’s (Amy Ryan) home after being hit by Grace’s truck. Roger is a doctor and is able to care for Beau as he recovers from his injuries, internal and external. The relationship between the viewer and the protagonist seems to lessen as we learn more about the world at large. Yet what starts off as a kind suburban family becomes more and more estranged as Beau starts to unravel the oddities running behind the family. He is adamant to return home after learning that his mother wouldn’t be buried until his arrival. Roger promises to take him home, but Beau’s fear of being an inconvenience is met by Roger’s busy schedule. Beau’s stay at the home extends; with this extension comes the unraveling of the family’s odd behaviors. The thematic concerns of technology and time are heightened; Beau blanks out for extended periods of time, and the movie compensates for the time gap through fast lighting changes from night to day, from day to night. Grace shows Beau the television that can see into the future, and he speed-watches the rest of the film. Roger and Grace’s daughter Toni (Kylie Rogers) is angry at Beau for interrupting their family life, blaming his presence as an attempt to integrate himself within the family. She drinks a gallon of paint in protest, dying in Beau’s arms as to blame him for the death. Beau’s unstable mindset makes him an extremely unreliable narrator. Packed on top of the family’s bizarre quirks and actions, the suburban scene establishes the role of the outside world as detached from Beau’s perspective as Aster will let the audience. However, the more Beau learns about the family, the more the audience sinks back into his mind.

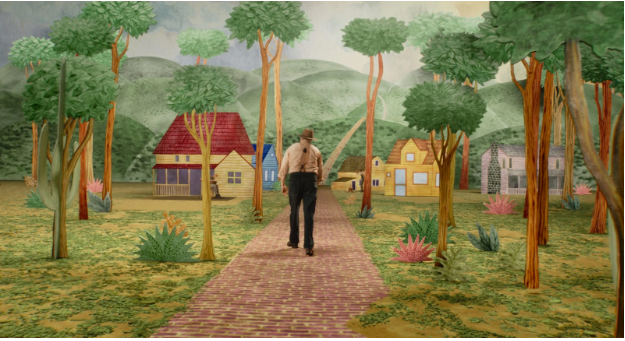

After being blamed for Toni’s death, Beau sprints into the nearby forest, stumbling upon a traveling theater company made of orphans. Feeling welcomed and at home, Beau watches their performance and becomes sucked into a hyper-surreal retelling of his own life; one where he learns a trade in a village, falls in love, and has three sons. The family is separated, and Beau’s journey turns into his desire to be reunited with his wife and children, strikingly different from his previous adventure of coming home to his dead mother. This journey is told through colorful animation, spoken aloud by an angelic voice as Beau stumbles along fictionalized villages, hand-drawn worlds, and fully masked faces. The audience has a hard time discerning what is and isn’t real. This part of the film is the most estranged and uncanny. Audiences are placed into a different adventure devoid of the previous two hours. The worldbuilding isn’t as saturated in detail as the previous two parts. It feels a little out of place, since the tone of the section is bright and optimistic, which clashes with Beau’s nature of being cautious and neurotic. Instead, the audience watches him embrace a dream he’ll never have. Aster also sprinkles in glimpses of Beau’s past and his potential love interest from when he was a child. His relationship with the world becomes a positive instead of a negative; it is one of the only times in the entire three-hour film where Beau is genuinely happy. Of course, this happiness is shattered as soon as he wakes up, and remembers who he is: a child of a mother recently deceased, a blamed murderer of a teenage girl, and a lost soul in the middle of an unknown forest.

The climax of Beau is Afraid is reminiscent of a sort of Judgment Day. Beau eventually finds his way out of the forest and back home, only to realize that he missed his mother’s funeral. He explores his own home, and through visuals, the audience starts to understand how impactful his mom was to the world at large. Marketing campaigns and corporation flyers lay scattered around the house, and the audience can begin to parse Beau’s dependency on technology to the invisible hand his mother held around him his entire life. Everyone Beau has interacted with in the movie, from Roger to his therapist in the very beginning, has a connection to his mom. Even Beau’s old love interest Elaine (Parker Posey) visits her home in memoriam; they share an intimate moment together, which is soon broken once Beau’s mom (Patti LuPone) finds them in her bed. The audience learned that she staged her own death to put to the test just how much Beau loved her. The entire movie, from the very beginning to their reunion, was an evaluation of Beau’s love and care. His actions were seen as a failure; every hesitancy or moments of skepticism towards going home was used against him in a staged court within a coliseum, watched by the eager eyes of thousands.

Beau admits that he never believed his father really died, to which his mother brings him to an attic and shows him a phallic monster hiding away in the shadows; this is Beau’s father. The climax wraps up each detail sprinkled throughout the film. From Beau’s fears to his dreams, his turbulent relationship with his mother and the world itself are all understood in the last ten minutes, where Beau sits on trial and is eventually blown up from his, to put it simply, lack of love. For a surreal film, this ending is open to all sorts of interpretations. The thematic concerns of motherhood are linked tightly to the world’s growing dependency on corporations and technology. There’s fascinating commentary on wasted time, paranoia’s parasitical effects on relationships, and what it means to be an orphan. While some sequences felt longer than others, there was never a dull moment in Aster’s newest film. It sits nicely with his other works; something daring, something bold, something surprising, something untold.